The unrelenting pace of climate-related disasters has public and private sector organizations trying to mitigate the impact of climate change. When it comes to food systems, most attention has been given to food production—how best to reliably grow food under changing conditions, such as increased drought, and to increase local food production, like growing produce in Boston instead of importing it from across the country.

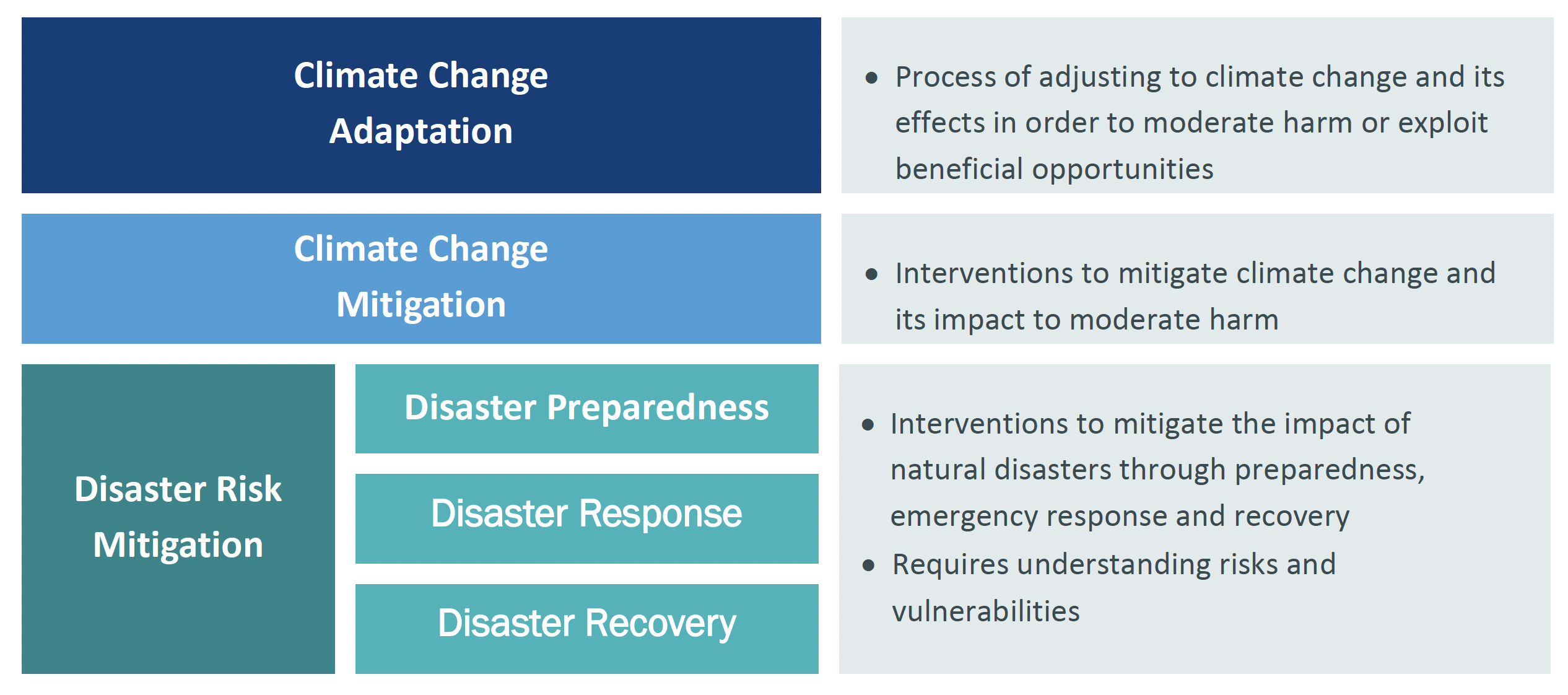

These efforts to adapt food production in the face of climate change are crucial, but they only address half the food system resilience equation in cities (Figure 1). At the Feeding Cities Group (FCG) we focus on the other half–ensuring food access in the aftermath of a climate-related disaster. For most cities, this is not a question of changing how or where food is produced, but rather or how and where food will be supplied to residents throughout a city. Given the increased probability of climate-related disasters, our disaster risk mitigation work is arguably more urgent.

Figure 1. Approaches to Addressing Climate Change

Kim Zeuli created FCG after a decade of working with cities—seeing firsthand the outdated and inadequate emergency food plans that most (if not all) cities have in place. Our mission is to help cities create robust emergency food plans tailored to the needs of their citizens and the unique vulnerabilities of their food system to natural disasters.

Creating an adequate emergency plan to safeguard food access will not only save lives after a disaster, but also money. It will also ensure that municipal food systems are more equitable for vulnerable, food insecure communities today.

FCG is currently identifying several North American cities at risk for severe climate-related disruptions to their food systems to serve as pilot planning projects. We will use these proof-of-concept plans to showcase the merits of our new model of emergency food planning – one that we believe can transform emergency food response and recovery as cities around the world cope with the soaring impacts of climate change.

Why current emergency food plans aren’t enough

Of course, most cities already engage in emergency response planning. Food, however, is typically one small component of these plans. In part, this is due to the fact that cities count on receiving significant aid after a disaster from outside groups, such as FEMA and the Red Cross. This may have been a safe bet in the past, but the capacity of these organizations is being severely tested now by the severity and frequency of today’s climate catastrophes. Cities and states will ultimately need to rely on their own resources to feed their communities.

In 2020, for example, the Red Cross provided food aid immediately to victims of wildfires in the state of Oregon. However, the organization relatively quickly turned over the feeding mission to the state, which did not have plans in place that anticipated the disaster.

According to Jeff Gilbert, who took over the emergency food response in Oregon and felt firsthand the impact of an inadequate plan, “In the beginning we didn’t have a response, we were very flat footed…we had no idea how to feed all the victims, with no contracts in place. There were 4,755 homes impacted. How do you feed all those people?” Jeff is a Regional Emergency Coordinator in the Office of Resilience and Emergency Management, Oregon Department of Human Services (ODHS).

Similarly, when Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017, FEMA already faced unprecedented demands on its staffing, resources, and budget from three major storms that had hit the United States in quick succession. Just two weeks before Maria, in fact, FEMA’s support for Hurricane Irma had depleted the agency’s supply warehouse in Puerto Rico. As a result, FEMA couldn’t immediately supply sufficient emergency food to the island residents.

It might be easy to dismiss the island’s crisis as unique. But, in fact, a climate disaster can turn any city into an island, cut off from its usual supply chains and resources. Take, for example, Boston, MA, which narrowly escaped Superstorm Sandy in 2012. Our research found that, as with other cities we have studied, most of Boston’s food (94%) arrives by truck. Boston has two designated truck routes, one of which – I-93 – is extremely vulnerable to flooding from coastal storms and sea level rise. And Boston is hardly alone. Our work has uncovered similar vulnerabilities in cities such as New York City, New Orleans, and Toronto.

In addition, emergency response plans typically trust that residents will require food aid for a few weeks at most – an assumption based on the relatively short length of past emergencies. But as modern natural disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina, demonstrate, food system disruptions may last months or years. Our work also shows these disruptions vary by neighborhood, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations that already have the highest rates of food insecurity.

What cities need instead

In sum, current emergency food plans are no match for today’s catastrophic climate disasters. Plans continue to prioritize aid from external organizations, such as FEMA, even as these organizations struggle to respond to an ever-growing slate of crises. Most plans woefully underestimate both how long residents will require food aid and the needs of vulnerable communities already facing food insecurity and climate injustice.

With their emphasis on local supply chains and self-reliance, won’t local and sustainable food systems solve these problems? The answer is yes and no. On the one hand, the resources and knowledge within local food systems are central to FCG’s emergency food plans. On the other hand, local food production cannot, by itself, feed entire cities in the wake of a major climate disaster. We simply don’t have time to scale up regional and local food production enough to feed small cities, much less major ones like Boston or L.A., before the next climate disaster strikes.

What cities need instead are Sustained Emergency Food Plans that emphasize a city’s own food assets and knowledge, recognize the need for extended aid and the chance for less external aid – all while explicitly considering the needs of vulnerable neighborhoods and populations. Such plans will not only allow cities to respond more quickly – saving lives – and use any outside aid and resources more strategically – saving money – should a natural disaster occur. They’ll also help build a more equitable and just food system at all times, for everyone.

Please contact us to learn more about our work.

Kim Zeuli can be reached at kim@feedingcitiesgroup.com